When Adam and Eve realized they were naked, they became acutely aware of their physical differences, and instead of celebrating God’s image in each of them, they felt shame. Their shame pushed them to conceal their differences, and they sewed fig leaves for clothes. This played out the narrative Satan had set forth — that maybe God was holding out on them and didn’t have their best interests in mind.

They learned to cover, to hide, and to see their differences as a means of separation, oppression, and shame. Suddenly, as a result of their disobedience, there was a hierarchy and a power struggle at work, and what was intended for good, beauty, and celebration was broken. And now, any time we reject a part of ourselves that makes us distinct — including our ethnic and cultural identity — it’s all part of this ongoing brokenness.

By thirteen, I’d learned to believe the lie whispered in my ear like the one the sly serpent told Eve and all the daughters after her: that to belong I would have to get rid of everything that kept me from blending in and hide all that colored me in as the full version of myself. I’d already learned to question the way I was made and whether the one who made me had good intentions in mind.

I believed that cultural assimilation would give me a way to belong and move through life with less shame, but instead of offering me belonging, it only isolated me further. My fig leaves not only separated me from my classmates and from true friendship, but they also distanced me from my family and all the things I knew as home.

When I was a child, my family made three trips to Korea. From the moment we set foot in the country, people stared at my sister and me with wide eyes. We were Korean blemishes, evidence of unrequited national love, honyol daughters in the motherland where pure bloodlines are sought after and protected at all costs.

How can I feel at home and foreign at the same time? I wondered.

On my first trip to Korea when I was seven, my parents and I went to a dinner party with my mom’s extended family and their friends. I was sitting in the front room with my cousins and a bunch of kids I didn’t know. One of the boys kept pointing at me. He was taller than I was, with smooth black hair cut like a bowl around his head.

When we all went outside to play, he poked me with a toothpick. I stared at him, then at the toothpick, too stunned and confused to understand why he’d do something like that. Everyone else was laughing, especially the boy with the secret toothpick. I tried to stay away from him, on the other side of the group of kids. My stomach turned when our eyes met.

I went inside to see my parents, but they were drinking and laughing, enjoying the other adults. I didn’t say what was wrong but stood quietly, wondering which adults were the toothpick boy’s parents.

“It’s boring for you in here,” my mom whispered. “Go back and play with other kids.”

I went back outside, and we all stayed there until it was dark. Every chance he got, the boy poked me hard — in the arm, in the back, in the neck, in my thigh — while I listened to the adults inside laughing.

When we left, I was so relieved I immediately fell asleep in the car. I never told my parents. Somehow, even as a first grader, I decided I was to carry the world of my mom’s loss, and both the worlds that couldn’t welcome me, in my tiny elementary-school body. I wanted to stay in Korea forever, and I also wanted to leave for fear of more round-faced boys who would poke my mixed skin with a dirty toothpick to remind me that I don’t belong.

Our story as sons of Adam and daughters of Eve isn’t just one of knowing God separate from our humanity and our own God-made bodies. God intends for us to know Him as we come to know ourselves. Our unique selves are to be studied, seen, uncovered, and sought with urgency. Knowing ourselves without shame is shalom in action — life unfolding the way it was meant to, the narrative of the Kingdom of God-come-down. In the midst of this, God’s dreams come true, unfolding detail by detail in our mothers’ wombs.

When God calls out to Eve and Adam after they’ve eaten from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, He asks them, “Where are you?” Even though He knows where they are, what they’ve done, and what the consequences will be, He seeks them out in their hiding.

He does this again and again. When Cain hides after murdering his brother, God finds him and asks him where his brother is. When Hagar runs from her oppressive life, He asks her where she’s come from and where she’s going.

God’s love will not let us go on hiding forever. His love finds us, stops for us, and searches for those who have been harmed and those who need healing.

And whenever we come near to someone else in hiding, we imitate Jesus, our Immanuel: the God who comes near.

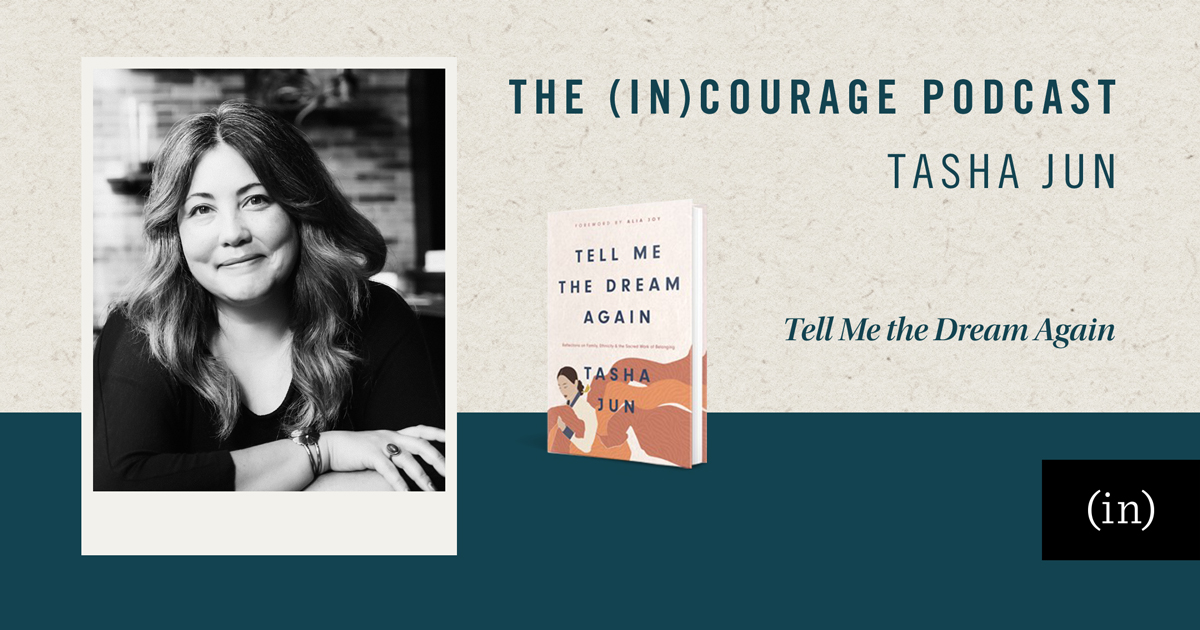

Adapted from Tell Me the Dream Again: Reflections on Family, Ethnicity, and the Sacred Work of Belonging, by Tasha Jun. Copyright © 2023. Used by permission of Tyndale House Publishers, a Division of Tyndale House Ministries. All rights reserved.

—

Told with tender honesty and compelling prose, Tell Me the Dream Again: Reflections on Family, Ethnicity, and the Sacred Work of Belonging, by Tasha Jun is a memoir-in-essays exploring:

- what it means to be biracial in America today

- the joy and healing that comes with embracing every part of who we are, and

- how our identity in Christ is tightly woven with the unique colors, scents, and culture he’s given us.

We are not outsiders to God. When we let all the details of ourselves unfold ― when we embrace who we were divinely knit together to be ― this is when we’ll fully experience his perfect love.

Order your copy of Tell Me the Dream Again today . . . and leave a comment below for a chance to WIN one of 5 copies*!

Then join Becky Keife for a conversation with Tasha this weekend on the (in)courage podcast. Don’t miss it!

Listen to today’s article at the player below or wherever you stream podcasts.

Thank you for sharing and for the opportunity to win a book.

Glad you are here, Nadine!

As a Korean immigrant, I can totally relate to the feelings you had as a kid. Thank you for sharing your story and also for giving us the opportunity to win a copy of your book.

Thank you for this! I agree that cultural assimilation is not the answer—which is a sign of our “ongoing brokeness” (the effect of sin). It is only temporary. A bandaid. A “sweep it under the rug” sort of thing. Sooner and later our pain and aches comes back.

This is a sign that we are all in deep need!

So yes, the answer is Christ! Our identity in Christ always trumps and comes first over all other: over language, culture, ethnicity, nationalism, and race. And that is the most freeing thing because Christ gets to say who we are; not the world.

Because of that we have the freedom and peace see ourselves the way God sees us: beautiful, unworthy but worthy, broken, but made GOOD. Blood isn’t thicker than water! Because we belong in this thing called the spiritual family of God. We’re all adopted! You and I are closer because we are children of God than how we are related ethnically to people who look like us. We are family in Christ.

And I agree— we don’t feel like we truly belong because we really don’t belong. The world isn’t our home.

With eternity in perspective, all of our culture, language, skin color, ethnicity— all is going to fade away. And when we die… this world’s identity for us dims significantly to nothing. What matters most is how God sees us. And he sees us as made Good and redeemed through his Son, Jesus.

I’m Hmong American and I was hit with the dilemma: preserve my cultural roots or “assimilate” in America. I chose neither!

I chose to preserve the gospel first. Seek the Kingdom first and all else will follow.

It wasn’t until then that I said, I love this part of being Hmong; and any cultural practice of being Hmong that is ungodly, I renounced. The same came along as being an American. I love being the American I am, but not all of it is good.

God, You get the last say in who I am. If this hard road leads me to you, then I will walk through it if you want me to.

Thank you for sharing your story, Houa, and for a glimpse of what it looks like for you to carry the layers God has given you to consider and carry with your story as a Hmong American.

One thing that I love when thinking about eternity with God, is that we will be with God and bring our divinely given ethnicity with us as the vision is described by John in Revelation 7:9 , “After this I looked, and there before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and before the Lamb. They were wearing white robes and were holding palm branches in their hands.” Won’t it be so beautiful to witness the imago Dei in each of our ethnicities as we worship together?

So glad you are here.

Amen, sister!

I believe that!

Sorry! I did not mean to reply to your comment, but to make a comment to the post here. I think I pressed the wrong button. My phone scrunched up the web page. I apologize!

But I appreciate your comment nonetheless 🙂 I too can relate!

I’m so glad you are here. Thank you for letting me know that the feelings shared resonated with you.

As a biracial individual myself I feel so much of what Tasha spoke to in this post! Definitely plan on reading this book!

Emily, I’m so glad the post reached you and that you can resonate. It’s a unique story we carry. I’m happy you’re here!

You are beautiful inside and out! Keep shining your light for all the world to see Jesus in you!

Thank you, friend.

Tasha,

My heart breaks for your little girl pain. Though our experiences are different, I remember how others treated me in hurtful ways, how those instances informed how I saw myself.

I’m SO thankful God can redeem everything in our lives, in His time, in His ways. Your book is going to be such an encouragement to help readers see Him in a way that ushers in Shalom…and the way we see ourselves in light of who He is. What a gift!

Those things stay with us for a long time, don’t they? I’m grateful for healing and for the ways God pursues us and cares about the mending and liberation, no matter how long it takes us to receive it.

Yes we are all same but yet different in our own ways in Jesus. As we all have our own personality’s that Jesus has given each of us. We are all Brother’s and Sister’s in Christ. There to help either and love either the way Jesus helped and love us and still does. Even though we are same yet different as we belong to one big Family the Family of God. That is so good to know. We are all Brother’s and Sister’s in Christ to be there for either. What make us different is our looks and where come from. But we all have the same and one Heavenly Father who loves and cares for us and cares for us enough to call us his children. We can him our Heavenly Father. Our Heavenly Father goes on to call us more than his children but Daughters of the king. That is so nice to know. He loves us for who we are he is glad to be our Heavenly Father. He loves us so much he sent his son to die for us. No greater love was that. Thank you Tasha for what you wrote so true all what you said. Love Dawn Ferguson-Little xx keeping you all incourage in prayer

Thank you, dear Dawn.

In reading today’s “In Courage” selection by Tasha Jun, my thoughts drifted not only to the rejection of ethnic and cultural identities, but of all being made in God’s image. “For You created my inmost being; You knit me together in my mother’s womb.” Psalm 139:13

ALL are created in God’s image. Acutely aware of their physical and emotional differences, many in the LGBTQ community conceal their true selves and own the shame thrust upon them by a society intolerant of any differences. As the author states, “any time we reject a part of ourselves that makes us distinct . . . it’s all part of this ongoing brokenness.” Further, she realized “that to belong I would have to get rid of everything that kept me from blending in and hide all that colored me in as the full version of myself.”

Many in our society today are finally breaking the shackles that bind them and coming out of hiding.

Let us imitate Jesus, our ultimate teacher, and “Judge not, lest you be judged.” Matthew 1:1

Kathy, thank you for your thoughtfulness and for sharing your thoughts with us. I can tell that you have a deep well of empathy and that you think about the belonging and welcome of all people. I’m so glad you are here and that you are in the world.

I have seen your book out, about, and being talked about. Sounds so interesting! Thanks for sharing this today. I have a tendency to hide myself and am trying to teach myself not to do that. Someone recently told me, “I know you must have been taught to be small somewhere but we need you!” What a gift that person was to me when she said that. Thank you for another opportunity to win!

Heidi, may Love keep leading you out of hiding. I know how terrifying it can be to revisit the reasons and to show up whole. It will take the time it takes, but your friend is right – you are needed. We’re so glad you are here in this community.

I was praising God this morning for His beautiful creation and marveling at how he created every person that has ever existed unique. Every one of us is different yet He knows us inside and out. He loves each and every one of us more than we can comprehend. Sin separates us from God and each other but the Holy Spirit binds us together in love.

I appreciate your candid sharing. We live in a broken and evil world,where we become targets due to our faith in CHRIST, our race, ethnicity and culture. Our Creator made us as individuals to embrace ourselves and live for the LORD.

It’s certainly getting harder for believers to be accepted in this “upside down” world where right is wrong and vice versa.

My hope is in CHRIST, and I shall continue to follow HIM wholeheartedly. I will continue to witness for the LORD by being supportive, loving, kind and understanding to others who are different from me. I have many opportunities to do so in the country I live in.

One day, we will rejoice in the new kingdom established by the LORD. All praise and glory to the King of kings and LORD of lords. Meanwhile, let us remain steadfast in the LORD who is the same yesterday, today and forever.

Thank you Tasha for the beautiful reminders that we are created in God’s image, and also for giving us the chance to win copies of the book. I already know who I would gift the books to. I love this safe space to encourage and hear peoples’ experiences in a God centered platform. I wish all platforms were this (in)couraging!

Thank you for sharing your heart with all of us today. I appreciate hearing so many different voices. It’s one of my favourite things about (in)courage. All of us have voices that need to be heard and identities that need to be celebrated. I’m so grateful for the opportunity to learn from so many wonderful women.

Tasha,

It’s sad that people treat each other with such disrespect-especially little children. They are usually more accepting than adults. Why can’t we all just love each other like Jesus? We seem to forget that each of us ALL nations, cultures, etc. were created by the same God & in His image. We need to respect & come alongside anyone in hiding. Love on them as Jesus would.

Christ has redeemed people “from every tribe and language and people and nation.” In Heaven we will have a multi-ethnic group gathered around the throne praising God. This will be a super encouragement to many.

Blessings 🙂